Text by Jonathan English

Updated and Revised by James Bow

|

|

A map showing the first phase of the Downtown Relief Line as proposed in 1984. Only Queen East and St. Lawrence (at Sherbourne) are confirmed stops in the original plan. |

The Downtown Relief Line goes by many names. In 2016, some refer to it as the Don River Line, or the Yonge Relief Line. Though, as of its writing (April 2017), it amounts to nothing more than a shelf-ful of studies, it has a history going back over a century, when it was originally referred to as the Queen Street subway.

A full history of the Queen Street subway can be read here. Growing from proposals in the early 1910s when Queen Street was the major east-west thoroughfare in Toronto, it was in the late 1940s and early 1950s the second priority for subway development after the YONGE subway line. In the mid-to-late 1950s, when the TTC realized that suburban traffic was increasing on Bloor Street and Danforth Avenue, they proposed to delay construction of the Queen subway and build a line under Bloor Street and Danforth Avenue instead.

After much debate, including a proposed “Flying-U” compromise that would have seen the subway built beneath Queen from Trinity Park to Carlaw, before turning north at both ends towards Bloor-Danforth and turning out towards Etobicoke and Scarborough when it got there, the BLOOR-DANFORTH subway was built as is, and the Queen line faded as a priority, especially as the balance of power shifted from the original city of Toronto to the suburban municipalities of Metropolitan Toronto following a provincial re-organization in 1967. When plans were finalized to build the SPADINA subway, the Queen subway was listed as a priority, to open in 1980, but that was the last that Toronto heard of this project under that name.

The Downtown Needs Relief

After 1980, Instead of the Queen subway, attention focused on an upstart proposal to connect the BLOOR-DANFORTH subway at Pape to Union Station. The Downtown Relief Line (or Downtown Rapid Transit/DRT) was one of three new subway routes proposed in the early 1980s as part of the Network 2011 plan. Along with a Sheppard Avenue subway running from an extension of the Spadina line to the Scarborough Town Centre, and an Eglinton West subway running from Eglinton West station to the Mississauga border, the Downtown Relief Line would relieve the overcrowding on the Yonge subway, particularly at Bloor-Yonge station. At the time, Bloor-Yonge station was already operating above its design capacity.

The Network 2011 proposal was a blueprint for subway construction from 1984 to 2014, carefully crafted for the political realities of Metropolitan Toronto at the time. The two-tier municipality was made up of the old City of Toronto and five suburban municipalities, Etobicoke, York, East York, Scarborough and North York. All were very eager to ensure what they saw as a fair distribution of subway construction, and so the three lines were meant to spread subway construction and development around Metropolitan Toronto, while at the same time staging the projects’ construction for ease of budgeting.

The first phase of the SHEPPARD subway, from Yonge to Victoria Park, was given top priority (to open in 1994), and the Downtown Relief Line was priority number two, scheduled to open in 1998. The line avoided Queen Street for a number of reasons. Some plans called for the line to follow the railway lands to Union, saving money on tunnelling beneath Queen. Union Station was also at the centre of a proposed multi-billion dollar redevelopment of the railway lands, including the SkyDome, and it was thought that the Downtown Relief Line could help anchor that redevelopment. Some plans called for the Downtown Relief Line to be operated with ICTS technology, like the SCARBOROUGH RT, with the line swinging off of the railway lands on an elevated guideway and entering an elevated station in the middle of Front Street between Union Station and the Royal York Hotel.

When the Network 2011 proposal was drafted, subway technology was favoured, and the first phase of the Downtown Relief Line would have operated from Pape station on the Bloor Danforth line, via south on Pape Avenue to Eastern Avenue, where it would turn west and operate beneath Eastern Avenue and along the railway right of way until it dove under the rail lines north to Front at Union Station. It was then planned to have continued west to Spadina Avenue.

The route would be an extremely quick trip Downtown, with the trip from Pape to Union featuring only two intermediate stops between Pape and Union (Queen East and a stop near the St. Lawrence Market), compared to the ten stops passengers currently wrestled with on the BLOOR-DANFORTH and YONGE lines, making the Downtown Relief Line an enticing diversion from the overcrowded Bloor/Yonge station. In the Network 2011 report, the cost of the Downtown Relief Line, including a new yard to store and service trains, was listed at $565 million.

All the planning was for naught, however. The Network 2011 proposal failed to make traction with the provincial government following the retirement of Premier Bill Davis. A change of government from Conservative to Liberal resulted in further delays, and the price tag for construction ($2.1 billion for the whole network in 1985 dollars) had the new government searching for cheaper alternatives. Then, a recession and development collapse in downtown Toronto in the early 1990s reduced TTC ridership by more than 20%. Suddenly the crowds weren’t as pressing on the YONGE subway line, and neither was demand for downtown relief.

The Proposed Route (in 1985)

In the first phase, the Downtown Relief Line would travel south from Pape Station underground to an optional station at Gerrard. The Pape-Gerrard area was designated as the district’s commercial centre. Further south, a station at Queen Street was planned, to reduce the very heavy traffic on the streetcars into downtown Toronto, particularly the bottleneck between Broadview and King.

A yard was proposed at the southern end of Pape at Eastern Avenue, bordered by the Gardiner Expressway, Heward Avenue, Winnifred Avenue and Eastern Avenue. After turning west, the line would join the Kingston Sub railroad right of way where it would travel on an elevated structure akin to the Scarborough RT. It was planned to descend to grade level roughly at Cherry Street, and the next station would be at Sherbourne Street, and would likely have been named St. Lawrence.

At Church Street, the line would have returned underground, passing underneath the railway tracks at Yonge Street, and stopping at Union Station directly south of the existing station. To the west, a stop was planned at the Convention Centre, and finally at Spadina, both underground near Front Street. These stops would have served the western railway lands developments, especially the SkyDome, and would have prevented a bottleneck of terminating trains at Union Station.

|

|

This map shows the possible western extensions. Three options were identified. |

The initial plans for the Downtown Relief line suggested three possible alignments for a western extension from the Front-Spadina intersection. All three would have pushed west from Spadina underground along Front to Bathurst (where a station would be placed) and then elevated in the median of a Front Street extension to Strachan and a station near the Exhibition grounds.

From Strachan, the cheapest route would follow the railway right-of-way past the Exhibition and up to the Galt-Weston railway corridor which it would take to Dundas West station. Although the least useful of the three alternatives, it still provided a quick trip from the BLOOR-DANFORTH subway downtown for Etobicoke residents, and offered up the possibility of a quick extension to Eglinton Avenue and possibly Pearson Airport via the Weston subdivision.

Another alternative would push west from Strachan along the Oakville subdivision to Roncesvalles, where it would turn north to connect to the Bloor line at Dundas West. Stations along this alignment were planned at Jameson Avenue, the Queen/Roncesvalles intersection, Howard Park, and Bloor Street. This was the recommended alternative, as it would serve more people and connect with streetcars coming in from Lake Shore Boulevard and the Queensway, giving southern Etobicoke residents a quicker trip downtown. It is doubtful the residents and businesses along Roncesvalles Avenue would have favoured this extension, however, given the disruptive construction required.

Finally, consideration was made to run the line along an elevated guideway on Parkside Drive at the edge of High Park to the Keele Station. This alignment would have been very unpopular because of its effect on the park and the surrounding residential neighbourhood, but it remained attractive because of the costs saved from not tunnelling beneath Roncesvalles.

|

|

The Borough of East York was a strong backer of the Downtown Relief Line plan, and this is why. |

At the east end, the Downtown Relief Line could have been extended north of Pape station, crossing the Don Valley either beneath Leaside Bridge, or via a new structure. The line would then travel along an elevated guideway in the median of Overlea Boulevard and Don Mills Road, terminating at Eglinton, giving Thorncliffe Park, Flemingdon Park, and the Ontario Science Centre subway stations. An underground station would also exist at Cosburn and Pape. The relief line could conceivably have continued farther north as far as Sheppard, making a connection with the SHEPPARD subway, although whether or not it could have done this above the median of Don Mills Road or beneath it is open to question.

The Downtown Relief Line Rises From the Dead.

The Downtown Relief Line proposal languished since the early 1990s, as ridership across the system fell and congestion at the Bloor-Yonge transfer station diminished. The situation started to reverse itself in the late 1990s, however, and by 2001, the TTC began to notice that stations on the southern section of the Yonge line were becoming congested.

In 2001, Toronto City Council directed the TTC to draft a Rapid Transit Expansion Study, to identify which subway extensions should have priority should funds become available from the provincial or federal governments. The people who drafted the report recommended a two-station extension of the SHEPPARD subway east from Don Mills to Victoria Park, and a northerwesterly extension of the SPADINA subway to York University and Steeles Avenue. They identified extending the YONGE subway north to Clark Boulevard (one kilometre north of Steeles Avenue) as a strong option that could generate more riders than the other two options, but failed to recommend it, saying:

While the Yonge Subway options rank higher than most options, a northerly extension of the Yonge Subway line has the potential to overload the Yonge line. From an operational perspective, it would be more prudent to better balance ridership on the Yonge and Spadina Subway lines by first extending the Spadina Subway north of the current Yonge Subway terminus at Finch Avenue. By extending the Spadina Subway first, approximately 2,000-2,500 AM peak period (6-9 a.m.) riders on the Yonge Subway can be off loaded to the Spadina Subway line thereby providing significant relief to the Yonge line in the medium term.

Activists and politicians noticed the reluctance to extend the YONGE subway, and further plans to increase the capacity of the YONGE subway, and speculated on whether or not the Downtown Relief Line proposal might return. In 2007, as the TTC and the City of Toronto embarked on its Transit City proposal to build LRT lines to the northern, eastern and western ends of the city, it was noted that there was little increase in the capacity of transit services downtown. Finally, in 2008, TTC Chairman Adam Giambrone speculated that a Downtown Relief Line might become a necessity, although he didn’t foresee it being built until after 2018.

Speculation increased as Metrolinx, the transit planning agency mandated by the province to draft a long term plan to improve public transit throughout the Greater Toronto region placed the Downtown Relief Line (or a Queen subway) in its most optimistic proposals, with construction to take place in 25 years. Further, they pressed ahead with a proposal to extend subway service on the Yonge line north from Finch station to Richmond Hill at a cost of $2.4 billion.

The TTC and the City of Toronto worried that the YONGE extension would significantly increase congestion problems on the southern part of the YONGE line. Even with automatic train control, new trainsets and a seventh car added to trains, even Metrolinx estimated that the Yonge subway would be 40% over capacity by 2031. In late January 2009, Toronto City Council approved the extension of the Yonge subway, with preconditions, including expansion of the Bloor-Yonge transfer station, that could inflate the total cost of the YONGE subway extension to over $5 billion. At the same meeting, city councillors approved a motion to encourage Metrolinx to give a higher priority for the Downtown Relief Line, which could solve much of the capacity problems caused by the Yonge extension, while expanding rapid transit service to a wider portion of the Toronto core.

Political Issues and Downtown-Suburban Animosity

It is important to note the political issues that surround the construction of the Downtown Relief Line, especially in terms of relations between suburban and downtown residents. The Transit City proposal focused on extending LRT services to the suburbs without addressing downtown transit needs because, it was stated, this prevented a large-scale downtown subway project dominating the conversation, and possibly preventing the needed LRT lines from being built. It was only when the prospect of the YONGE subway becoming overcrowded south of Eglinton Avenue with the proposed extension to Richmond Hill that Toronto City Council started to advocate for the Downtown Relief Line.

Even then, city politicians counselled against the monicker, preferring to call it “the relief line” or the “Yonge relief line” to prevent suburban residents from thinking that this line benefitted rich downtown residents disproportionately, enflaming jealousies. When Rob Ford became mayor of Toronto in November 2010 on an anti-LRT, anti-downtown platform, he did advocate for a Downtown Relief subway line, but only after subway lines were built beneath Sheppard Avenue East and Finch Avenue West.

The cost of the Downtown Relief Line remains an impediment. Unlike the rest of the Transit City proposal, the Downtown Relief Line will likely have to be a subway, and a large portion of it will have to be tunnelled. This pushes the cost of the project into the billions, and that has politicians scouring for cheaper, if less-effective alternatives. One such alternative was SmartTrak, proposed by John Tory during his mayoral bid in 2014. Using electric trains on already existing railway rights of way, he argued that an above-ground subway line could be built from Unionville on the Stouffville GO line, down through Scarborough and along the Lakeshore GO line, through Union Station, and then up the Weston sub and beneath Eglinton Avenue to Pearson Airport. The infeasibility of this plan, and the fact that trains operating at fifteen minute intervals are unlikely to provide the relief required gradually faded the SmartTrak proposal from prominence.

The Road to Relief

In 2012, the City of Toronto and the TTC launched the Downtown Rapid Transit Expansion Study, to reconsider the potential alignments of a relief line connecting the downtown with the subway at Danforth Avenue. Metrolinx affirmed the line as part of its “Next Wave” of transit projects to work on after its current batch were built. The province of Ontario showed further support by providing $150 million for a detailed design and engineering study, and public consultations on the project began in April 2014. A short list of alignment options was provided for public consideration in June 2015, and the preferred corridor was identified and approved by Toronto City Council on March 2016.

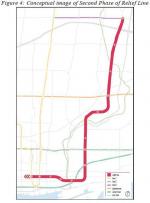

And this route took the Downtown Relief Line back to its roots. Following the footsteps of the original cross-town subway plans and the Flying-U compromise over fifty years beforehand, the new relief line alignment approved in March 2016 would see trains start from Pape and Danforth and tunnel south on Pape, southwest beneath the Gerrard Square mall, south on Carlaw, west on Eastern, through the West Don Lands before curving northwest to Queen Street and continuing to University Avenue. Intermediate stops would be at Gerrard, Queen/Carlaw, Broadview/Eastern (serving the redeveloping Unilever site), Sumach/King, Sherbourne/Queen, Yonge (City Hall) and Osgoode station. The Queen subway had been reborn.

There remained possibilities for further extensions. Metrolinx noted that the line could offer improved relief for the Yonge subway if it was extended north from Danforth Avenue to the Eglinton/Don Mills intersection, and possibly even running as far north as Sheppard Avenue.

Although the alignment had been worked out and approved (barring minor variances), funding had not been secured. In April and May 2017, Toronto Mayor John Tory spoke strongly against the provincial government for failing to provide funding in its budget to start construction of the line ahead of the YONGE extension to Richmond Hill. However, as of this writing (April 2017), the final decision on when work should begin on the Downtown Relief Line has not been made, and the issue is still in flux.

A Question of Will

There are few, if any, politicians or government organizations, who would argue that the Downtown Relief subway line should not be built, but few people agree on when construction should start, and how it should be paid for. This has become particularly pressing after a report released in May 2017 stated that the preferred alignment with eight stations would cost $6.8 billion.

In this respect, the Queen Subway/Downtown Relief Line echoes the saga of the Second Avenue subway in New York City. Initial proposals for its construction surfaced in the 1930s, and despite attempts to build the line in the 1970s, the first few stations of the line only opened to the public at the end of 2016. The Queen subway/Downtown Relief Line has been proposed for even longer, but the Second Avenue subway did finally get built, so that offers hope that Toronto may finally see construction eventually.

Document Archive

- TTC Downtown Rapid Transit Expansion Study, October 24, 2012 (PDF - 1.8 Mb)

- Metrolinx Yonge Relief Network Study, June 25, 2015 (PDF - 1.4 Mb)

- Presentation pages for a public meeting on the Carlaw-Pape alignment, March 2017 (PDF - 6.2 Mb)

Downtown Relief Line Image Archive

References

- A New Relief Line in Toronto. City of Toronto, n.d. Web. 09 May 2017.

- Howell, Peter. “NDP puts transit expansion on hold.” The Toronto Star 13 Oct 1990: pA?.

- James, Royson. “Politicians vying for the first crack at transit ‘dough’.” The Toronto Star 7 Apr 1990: pA?.

- Laver, Ross. “Rapid Transit: an issue so hot that politicians are putting it on ice.” The Globe and Mail 7 Sep 1982: pA?.

- Munro, Steve. “Posts about Downtown Relief Line on Steve Munro.” Steve Munro. Steve Munro, n.d. Web. 09 May 2017.

- Toronto Transit Commission, Network 2011: A Rapid Transit Plan for Metropolitan Toronto, The Toronto Transit Commission, Toronto (Ontario), May 1985.